I've encouraged my students to abandon books since I began encouraging them to find books they love. The logic is pretty clear, and we follow it with other mediums without a second thought: we turn off shows that don't entertain us and listen to a new station when music doesn't meet our tastes. There is something about books, however, that sets them apart. I didn't realize this until recently.

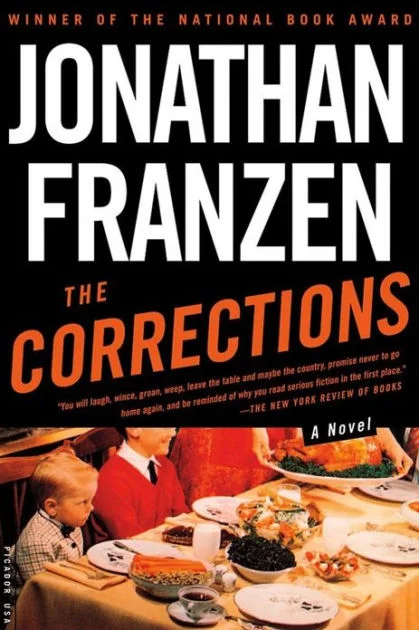

A fellow teacher suggested that I read Jonathan Franzen's The Corrections, and in exchange I gave a recommendation of my own (The Round House, by Louise Erdrich). I have had a copy of Franzen's novel on my own shelf for years, but buried amongst a pile of other books on my to-read list, it was a long way out from getting my attention. This recommendation, the trade, and the little "Oprah's Book Club" emblem on its cover were sufficient reason to make it a priority. At 500+ pages it wasn't a book that I would be able to consume quickly - not in the spaces between teaching and having a family - but I fixed in the drawer of my mind under the category of things "worth doing," a list of items that includes reading Kafka and watching Kaufman, filed in before the subcatagory "worth doing well," which includes high school art projects, yardwork, and writing a letter to your mother.

I struggled almost immediately.

If The Corrections was directly translated into a film, the opening establishing shots would be a series close-ups on largely disparate objects presented without context. Each shot cut together quickly, almost too brief to comprehend, each image accompanied by an amplified, abstracted sound coming from the object in frame. This is the Jason Bourne fight scene of establishing shots, and in text it presents itself as a thick paragraph of fragmented descriptions.

These bundles of words do not clearly build a character, a setting, or a conflict, and only in reflection do I realize that they actually build a tone. Each one is unpleasant, each one isolating, each one unremarkable, but in total they create a despair not just in their choices of words, but in the fragments themselves; as a reader, I felt like there was nothing of substance for me in those few fragments, but then I suppose that was the point. The character's that are introduced are similarly unremarkable at first blush: an old man with his mind on the glory days of a more orderly, purposeful past; his wife, woman committed to the commitment of marriage and managing everyday household affairs; their son, a pretentious college professor whose childlike rebellion against his parents resulted in an inflated sense of self.

“The Madness of an autumn prairie cold front coming through. You could feel it: something terrible was going to happen. The sun low in the sky, a minor light, a cooling star. Gust after gust of disorder. Trees restless, temperatures falling, the whole northern religion of things coming to an end. No children in yards here. Shadows lengthened on yellowing zoysia.”

These sterile introductions created a setting and characters that were not particularly interesting. As they developed I learned that they were in many ways deeply flawed, but they were flawed in ways that discouraged me from investing or caring about them at all. Even the diction that Franzen chooses - words like zoysia, gerontocratic, protoplasm, corpuscular, hitherto, précis - seems intended to create a distance between the reader and the characters.

This distance was ultimately insurmountable for me. As the narrative continued, it became clear that there was not really a plot here. There were events happening in sequence and there were even conflicts, but these things were all centered around characters that possessed almost no redeeming qualities, and as the novel continues there never seems to be any possibility of redemption for them. The characters - arguably - only become more deplorable.

I found myself on page 338 eventually, but it had taken me nearly two months to get there. I had become stubborn; I had decided that I am going to finish this book! But I wasn't enjoying it, and as a result days were passing before I would crack it open, two weeks in the longest stretch. Eventually I remembered the advice I give to my students: if you are not anxious to read it when you have free time, it isn't the book for you right now.

So I stopped, and I really did feel defeated. I felt like I had lost. This is a feeling that I've seen many of my students struggle with, and I have had a number who feel like this a majority of the time when reading. These are the ones that tell me that they "don't read." The best, most perfect, unabashedly honest description for it is to say that quitting a book kinda sucks. I am a confident reader, and have read hundreds of books in my life; if I feel like this, how much harder is it for my students, already struggling with adolescent feelings of inadequacy?

“I felt like I had lost.”

When I took a moment to reflect on my response to abandoning The Corrections, I realized that books are unlike most other entertainment endeavors. Books are associated with learning, and learning with intelligence. As a result, when I give up on a book there is a part of me that feels stupid. Combine this natural insecurity with the pressure I put on myself to finish this particular book, it isn't surprising that I tortured myself trying to push through the irredeemable characters. The book seems to want to say something casually disgusting about the nature of humanity - as if normal people are often terrible people when they are honest with themselves - and that just was not a message or a method of delivery that I wanted right now.

Possibly the worst part of ending Corrections a little more than half way through was that I doubted a part of who I am. I never really considered that maybe I was stupid, but I did wonder if maybe books were no longer something I loved. I am a champion of reading at school, a collector of books, and am rarely more fully sustained than when I am engrossed in a good narrative; but if books were no longer something I could readily digest, I thought maybe I was losing a part of my identity.

So I'm setting this one aside for a while. It is no good for me. I may come back to it; despite how little I care about Franzen's characters emotionally, I do kind of want to know what kind of hell they damn themselves to. Until then, The Corrections is going to live on my shelf.

Meanwhile, I have found some stories and books that quickly disabused me of the notion that leisure reading is no longer a part of who I am. I can devour books. I can find books that I want to read at stop lights and during commercial breaks. Just not this one. Not now.