(Originally Published December 3, 2017)

2013's The Last of Us opens with a menu over a solitary window that is overgrown with leaves and creaking as wind blows through broken panes to flutter the thin, white curtains at its sides. The white paint of the frame is worn and chipped, and moss has begun to fuzz over it. The buzz of an insect darts here and there off screen, somewhere outside the window, past which we can see the angular forms of blurred buildings, likely lost to nature as well.

This image represents how long nature has been unchecked by human traffic and interference, where the natural world has thrived in the absence of a humanity decimated by a parasitic fungus that infects and then drives wild the minds of its hosts. Society has been almost entirely lost, and in the tradition of Heart of Darkness and Lord of the Flies, where civilization's moral leash fails to reach a barbarity emerges. The Last of Us is a violent, brutal game. And as filled as it is with acts of cruelty and desperation, it is just as emotionally wrought; its protagonists, Joel and Ellie, suffer both unspeakable evils to them in the name of lawless opportunism and unspeakable evils to others in the name of desperate survival. And yet, despite this, the image that opens the game and introduces its audience to a world already lost actually holds in it the game's resolution, and its only modicum of hope.

This hope is not something easily won in The Last of Us. Joel and Ellie have both lost and lose much. Each suffers emotional and physical trauma in the course of the game. By the end, the promise of a vaccine to the cordyceps virus that has reduced humanity to a few violent, factional enclaves seems lost, and Joel has potentially betrayed the trust of Ellie, his surrogate daughter.

But when the game ends, they are walking toward a community built on the bones of a dam that, with some engineering, promises energy and a return to some semblance of the life each survivor has left behind. But the lie which Joel tells and their walk to the dam is not actually the conclusion of this story.

Instead, only once the player returns to the opening menu screen is there a resolution. Again we see the window, still overgrown, still gently swaying with the curtains as the wind blows through, but set aside is a knife. This switchblade belongs to Ellie, and for the duration of the game it has been a constant companion; she plays with it, escapes enemies with it, kills enemies with it. This item of violence that has done, through necessity, much violence defines her character, a young girl of just twelve in a world where innocence is lost nearly at birth.

And yet, after the game has been concluded, her knife is at rest. Out beyond the window, past the breeze and the buzzing, the rushing of water can be heard. By all these signs it seems as though Ellie has found a space where she could be at peace, where she needn't carry a weapon on her at all times. For a character that I had grown an attachment to over the course of the dozen or so hours of gameplay, this was meaningful.

For all its phenomenal production - it sets the standard for character, environmental, and sound design; for emotional, captivating storytelling; for a verisimilitude in the presentation of characters and settings that show the effects of their world on them - on its release, there were some who were critical of the game's almost unrelenting bleakness. It never held anything back from its depictions of man at his most violent and depraved. And yet The Last of Us ends with a note of optimism. There is still room for hope in the world created by developers Naughty Dog. For all the craft they put into creating an emotional, violent, vulnerable, powerful character like Ellie, this small window is a small detail, but a hope that provides much needed catharsis.

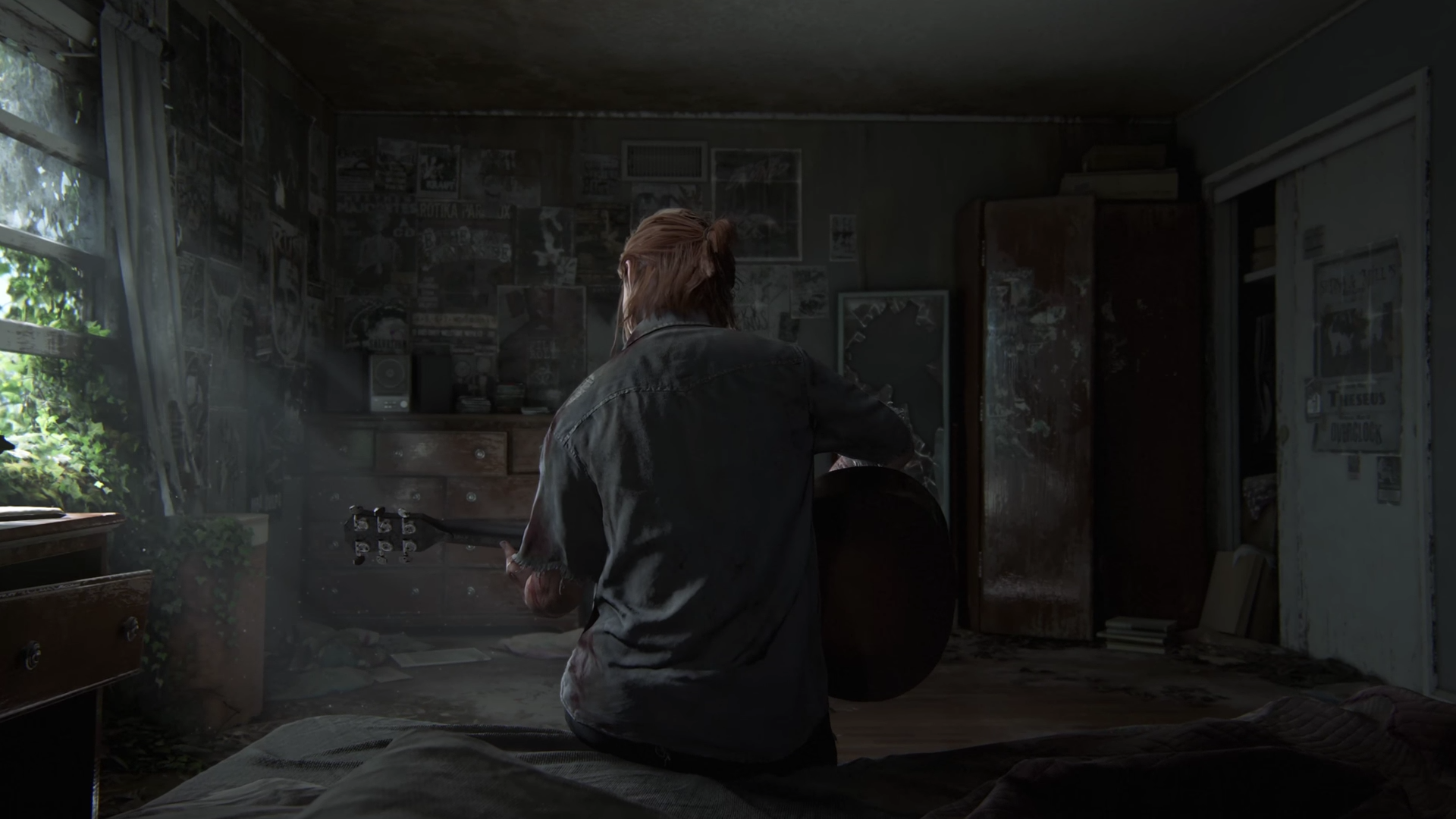

And then, at Sony's 2016 Playstation Experience conference, a sequel was revealed. It shows a house bloodied by violence as the camera tracks past the remnants of a deadly struggle. In the last room Ellie plays a guitar and sings, a haunting song about not fearing death, but knowing death well. She sits on a bed, and beside her the source of the room's only light, a window overgrown, framed by two thin, white curtains.

This is not the same window, but its appearance is familiar, a choice that alludes to the menus of the original game. For all the trailer's melancholic violence and unsettling musicality, it is this window that gets to me. Despite the beams of light that pour into the room, this window reminds me that there was once a space for hope in Ellie's life. 19 now, it seems that her hope has been violently quashed.

I cannot speculate what tore her from the community on the dam, but there does not seem to be room for little more than violence ahead of her. The Last of Us Part II does not appear to be a story of survival, like its predecessor, but one of retribution: as the trailer closes, Ellie stops playing to tell Joel that she intends to find "them," and kill every last one.

The Last of Us Part II has me excited, and dismayed. Naughty Dog is a masterful studio without compare and I am certain that this sequel will be not just a great game, but a great work of fiction. I will certainly enjoy the play of the single- and multi-player modes - actually, I've been craving something new in the online game lately; the stealthy intensity satisfies me in a way that maybe no other game does. I will also be engrossed in its tale, likely to be large in scale and intimate in its emotional resonance. Yet, I find myself disappointed by this window.

Poor Ellie. I am so happy to see you, but I wish it wasn't under these conditions. Good luck, friend.