On Slavery, the Civil War, and the Confederate Flag

A Facebook post that accidentally became an essay

There is a popular notion amongst a segment of the American population, which is certainly enthusiastic in their sharing of online memes and images, that asserts that the motivations of the South in seceding from the Union were unrelated to slavery, and that the emblems of that temporary nation were symbols of pride only. This position comes from a pride in heritage, people, and place that is natural, and to suggest that the motives of secession were anything lesser than the causes for the American Revolution would cast shade over those many Southerners that died, and the memories of those lost to war are precious to us.

This position, however, is wrong.

What follows will be an evidence-supported account of the motives that led to a war of brothers. I am cognizant of the fact that critics of my argument will suggest my sources are either biased or inaccurate, and for this reason I will principally rely on primary sources - the words of people alive at the time – as preserved in modern scholarship.

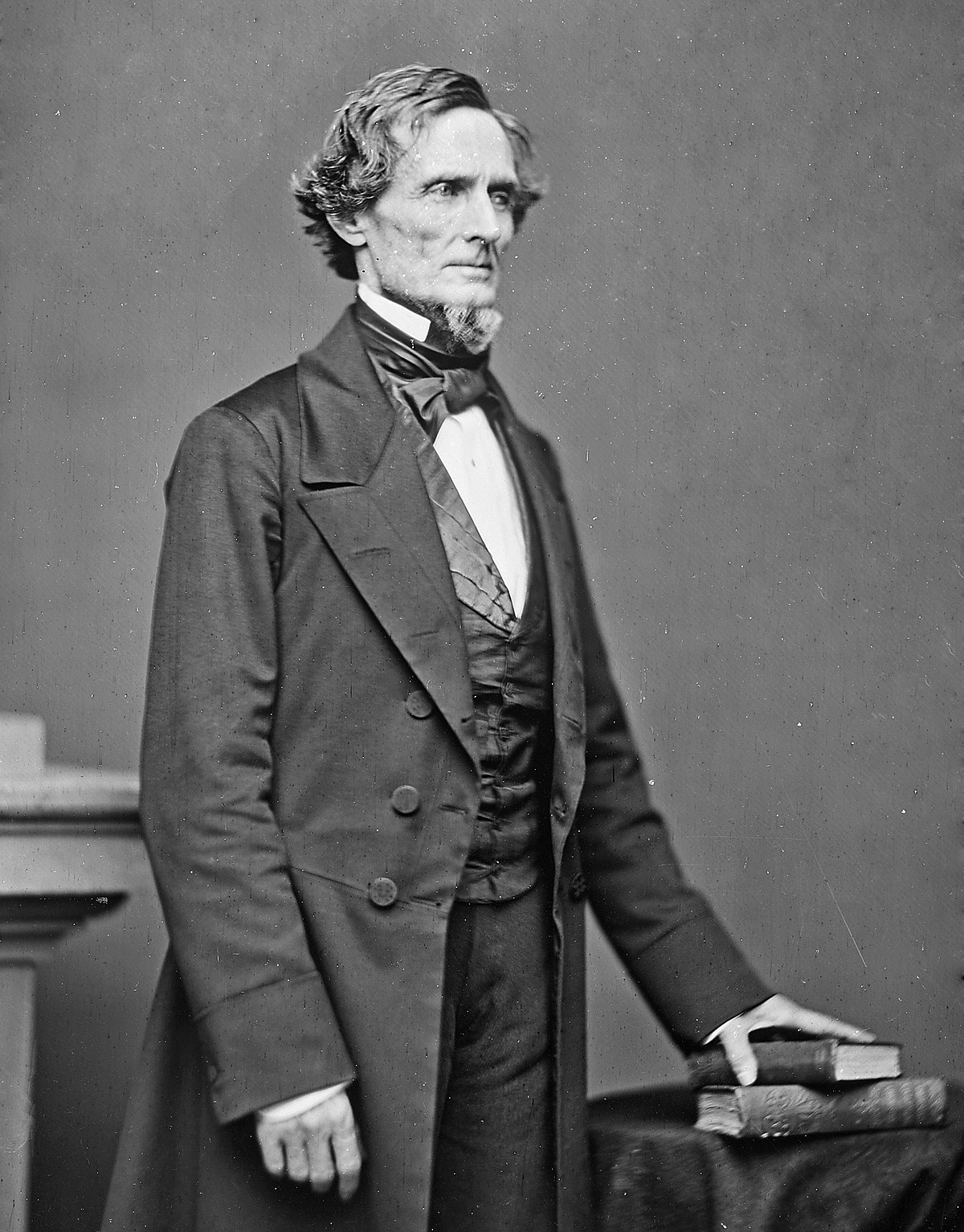

"African slavery, as it exists in the United States, is a moral, a social, and a political blessing."

Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America

Alexander Stephens, Vice-President of the new Confederate nation, said in 1861 that the foundations of the new nation “are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man.” In Stephanie McCurry’s Confederate Reckoning, this quote is later followed by one from the Confederacy’s future president, Jefferson Davis, who stated – before leaving the union – that “this Government [of the United States of America] is and ought to be, the Government of WHITE PEOPLE… Made by and fore the citizens – men capable and worthy to be free citizens” (22). It wasn’t simply that the Confederacy was formed on the basis of white’s essential superiority to blacks; rather, the assumption of Southern slaveholders was that the entire US nation was founded on this principle, and that the North was failing to live up to the promise of our founders.

But the South was not rallied together and enraged by this. It was disappointed. It felt abandoned, and many (including Davis), were staunchly pro-Union right up until secession. After Mississippi seceded, Davis noted that the Union had denied “the people” the “rights to which our fathers bequeathed to us,” later defining “the people” as those with the rights to govern. This excluded slaves, who were not “put upon a footing of equity with white men” (13-14). He was not alone in this idea that the Union had abandoned the white man, who was above the negro in every conceivable way, and it is important to remember that legally, Davis was correct: blacks were not a part of “the people” as identified in the Declaration of Independence. This was explicitly stated by the Supreme Court a few years earlier, when Dredd Scott failed to sue for his freedom from slavery.

But “the people” did not really include all whites. The secession of the South was not unanimous, because it was not particularly democratic. For one, Davis and others specifically identified citizens as a voting class, and in doing so ensured that women were not, constitutionally, citizens. They were the domain of their husbands. Of course blacks were excluded because they were property, but the white non-slaveholders were a whole other problem. Wealthy slaveowners loathed the slaveless whites, at least in part, because of their abject poverty and illiteracy. (There were no public schools; you had to pay for a tutor at home, which was impossible for the poor.) Southern legislators similarly despised them because they were a collectively powerful group as an electorate but who provided little economic advantage to the state, and these legislators regularly bemoaned having to pander to this demographic. Still, to secede meant a vote, and to get non-slaveholders to support the movement meant propaganda and force.

Fire-eaters - propagandists for secession - represented not just a powerful lobby, but an amazingly tactful rallying force, and had been pushing for secession since the early 1850’s. They invented the threat of imminent abolition to create a voting base around a fear of racial equity. (Of course, the North had little intention of doing this, and many abolitionists and important figures, including Abraham Lincoln, were plenty racist. The closest they came was arguing for popular sovereignty, which would have allowed new territories to decide if they wanted to allow slavery. But many thought blacks should be shipped back to Africa, Lincoln included.) But this propaganda was effective. It was threatened that the North, through abolition, would create “of our lovely land an American Congo” (McCurry 21). It was claimed that Black Republicans and their slave allies were going to rape good southern ladies (28), and fire-eaters were prophesizing a coming race war (29).

Side bar: it is important to note that the “Black Republicans” in the north were white men. They were referred to as “black” because of their perceived affections for Negros. Essentially, it was a way of identifying the north as abolitionist “nigger-lovers.” Truly, race vehemently, shamefully mattered.

Not all non-slaveholders were convinced however, because many in the South were still loyal to the Union. So in the late 1860 elections of South Carolina (and later in other states), armed companies of men and “hordes of [pro-secession] citizens dressed in blue cockade” (used to identify secessionists) lined the paths to the voting booths. The threat of violence was clear, as was the message: You. Must. Vote. This is clearly undemocratic, but the cascade of support was further suspect because besides being afraid of not voting, there were no pro-union options on the ticket: the South told every man to vote and only gave them options which meant secession. Some non-slaveholders voted with a blank ballot, but that was as close as they could come to trying to remain in the Union (49).

“We are under a reign of terror and the public mind exists in a panic.”

To reiterate, when voting on whether to leave the Union, a citizen of the south was required to walk past armed guards who expected voters to make a pro-secession choice, and when the citizen arrived at the ballot box, their only options were pro-secession. This is not democracy.

In that December vote, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union, and its “Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina” creates a clear picture for its reason for doing so. In paragraph fifteen, South Carolina points to the Fugitive Slave Clause of Article Four of the US Constitution, which guarantees that all states in the union will return slaves escaped from other states, then notes that “an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery, has led to a disregard of these obligations.” Essentially, by Northern States’ refusal to return escaped slaves, and by the federal Government’s inaction in demanding that Northern States do so, South Carolina had been wronged with a severity that merited secession. The document further finds offense that these states have “permitted the open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace and eloign [to take away] the property of citizens of other states.” The societies that so upset them were abolition groups, whose goal was ending slavery as a practice. This is basically the entirety of their reasoning: “permitting the escape of slaves and the presence of abolitionists who support them is not American!”

Not all of the seceding states issued a declaration which included causes; others issued ordinances which were to-the-point statements of action. Across all of these, “slave” was used ninety-eight times, either identifying slaves, slavery, slaveholders, non-slaveholders, or slaveholding states. It has become popular to argue that taxes and property played a predominant role in the secession, and this is partially true. Property was at the heart of secession, and that property was human chattel.

Taxes, not-so-much. For starters, those declarations and ordinances never once mention taxes. And when considering the grievances the Confederate states might have regarding taxes, apologists don’t have very strong ground to stand on. While the Confederate constitution – like the American constitution – guaranteed a citizen’s right to security in their property, the Confederacy did a pretty poor job of living up to that standard, as they created a 1/10th “tax-in-kind” law that allowed government Tax-in-Kind agents to enter any civilian dwelling and take possession of a tenth of anything available that could be used in the war effort, either directly or through its financial value (McCurry 155). The South’s tax policy was more aggressive and invasive than anything found in the North before secession.

The South entered the Civil War over slavery. It fired the first shots on Fort Sumter to start the Civil War, an action which was specifically suggested much earlier on by those secession-happy fire-eaters. But the North did not enter the war over slavery; it became engaged in war to maintain the Union. Despite some support in the north for an abolishment focus, Northern leaders were hesitant to make it a priority. There was still a significant problem with racism, and there was even a hesitance to put blacks into military service. Leon F. Litwack’s Been in the Storm so Long notes on page 66 that when finally Black Americans were allowed into service, they were given menial labor positions only, not combat positions – which would have suggested the equity of race the South was so fearful of. Only later, when it was clear to Lincoln and Northern generals that the war would not be easily won (both sides thought it would be), did they begin to consider the strategic advantage emancipation would bring, and it was for this reasons the slaves were emancipated across the US.

"The victory [at Fort Pillow] was complete and the loss of the enemy will never be known from the large numbers that ran into the river and were shot and drowned."

Nathan Bedford Forrest, Confederate General, on the slaughter of surrendering Union soldiers.

It will sometimes be said that slaves were being emancipated in the South, or that slaves were treated with some measure of dignity there, but this couldn’t be further from the truth. Even the rules of war were overlooked because of the South's animosity toward Black Americans. When Northern prisoners of war were marched through Southern towns, the confederate citizens were abjectly disgusted at the sight of black soldiers (Litwack 87). In war, an enemy surrendered becomes a prisoner of war and is afforded a certain degree of dignity and care. For black soldiers, and anyone who commanded or trained black soldiers, this behavior was ignored. Southern generals referred to all of these as “insurrectionaries” who were unworthy of prisoner status, and were generally executed. At what became known as the Fort Pillow Massacre, about 300 Union soldiers of a mixed race garrison threw down their arms and surrendered, only to be killed. Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest casually remarked that Fort Pillow was simply a place on the Mississippi River “dyed with the blood of the slaughtered,” the number of which “will never be known from the fact that large numbers ran into the river and were shot and drowned” (91).

Not only did the fervor of white supremacy influence secession and the disgusting brutality of the war, but it was pervasive in the South for years to come. After emancipation was forced on the South following their defeat, black codes, vagrancy laws, and employer’s agreements maintained a system almost identical to slavery. Blacks could not spend time beyond the limits of an employer’s land or risk arrest. They could not seek employment with someone else unless released by their current employer.

And as for what is known as the Confederate Flag, that battle flag that was adopted for two years as the national flag of the Confederacy (mostly because it was hard to distinguish Union and Confederate flags before due to their similarity)… Well, the original, square battle flag was created by William Porcher Miles — a fire-eater who advocated for ending the federal ban on the African Slave Trade — and Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, and used by the Army. Beauregard pushed heavily for the flag to be used to represent the Confederacy, and in ’63 it was officially adopted as the national flag, although the new version, modified by William Tappan Thompson, included a large white space around it. I’ll end with his comments on what the flag meant:

“As a people, we are fighting to maintain the Heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race; a white flag would thus be emblematical of our cause.[4]… Such a flag…would soon take rank among the proudest ensigns of the nations, and be hailed by the civilized world as the white mans flag.[5]… As a national emblem, it is significant of our higher cause, the cause of a superior race, and a higher civilization contending against ignorance, infidelity, and barbarism. Another merit in the new flag is, that it bears no resemblance to the now infamous banner of the Yankee vandals.”

![gettysburg-battle[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5137672de4b037a1b7ec0e44/1533333252715-OBIIK60W0FQYCIN1452L/gettysburg-battle%5B1%5D.jpg)